Design systems exist on a wide spectrum. Some consist of a style guide and a few components, while others are robust platforms with hundreds of components, multi-framework support, theming capabilities, and complex variable (AKA design token) architecture. The difference between these approaches isn't about ambition; it’s about understanding the product it serves.

Understanding where your design system should land on this spectrum is a challenge. If the system is too simple, users don’t have all the answers they need. Teams create individual solutions that result in inconsistent interfaces, duplicative efforts, and technical debt. It's tempting to build a robust system that provides more solutions, but over-engineered design systems can get in their own way: they're expensive to build, harder to maintain, and often unrealistic given timeline and budget pressures.

Design systems exist to provide digital consistency and efficiency. They should provide answers and enable our work rather than adding confusion or creating blockers. If we lose sight of this, we lose their purpose altogether. So, how do we get this right? It starts with asking the right questions, building a strong foundation, and adding complexity strategically only where it's earned.

Key scoping questions to ask

Start your design system project off by answering these key scoping questions.

What are we building?

Is this a marketing website, a SaaS product, a mobile app, or a multi-product platform? The nature of what you're building determines the foundation. A mobile-first consumer app has different needs than a desktop enterprise dashboard. Knowing whether you need responsive breakpoints, native platform conventions, or multi-theme support upfront helps you focus your efforts where they matter most.

Who will use it?

Your audience shapes everything about how you build and document. A system primarily used by engineers should prioritize clear implementation specs over reusable Figma components. Public-facing or open-source systems need much more documentation and governance depth than internal systems that are only used by a small team. Understanding your users determines not just what you document, but how much detail you provide and what format it takes.

Will it be maintained?

This might be the most important question because it fundamentally changes what you need to build. If your system is a one-off design created to ship a specific product with no maintenance plan, you need just enough structure to maintain consistency through launch—advanced variable collections and perfect component builds will go unused. If there is a plan to maintain it, your system architecture needs to be much tighter. Focusing on the foundation is key to promoting a healthy design system that has room to grow over time.

What's the growth trajectory?

Consider where the product or organization is in its lifecycle. An early-stage startup doesn't need the same architecture as an established platform serving millions of users, but you should understand the roadmap. Will there be launches on additional platforms? Are there plans to expand into new product lines? Will you need to support multiple brands? Knowing the likely path helps you avoid boxing yourself in or thinking too big.

What's the expected lifespan?

If this system will be used for years, investing in robust documentation and scalable architecture makes sense. If it's powering a short-term campaign or has a defined end date, simpler is better. Sometimes, business realities limit how long a system will be relevant. Acquisitions happen, products get sunset, and strategies shift. Understanding the timeline helps you adjust your investment appropriately.

What fits the timeline and budget?

Don’t forget to ask yourself: What can you actually accomplish with the time and resources you have? In an ideal world, you'd build exactly what the product needs, but the real world often has constraints. What will deliver the most value? What can wait until later? What is a need vs. a nice-to-have? Leaner projects with strict deadlines will need prioritized efforts to be successful.

What most design systems need, no matter the size

At the heart of every design system, there are a few foundational elements that are usually present:

- A color palette that includes neutrals and brand colors, built out into multiple shades

- Typography styles that define font families, weights, and basic hierarchy rules

- A unifying grid and spacing system

- A component library containing reusable UI elements (buttons, links, icons, form inputs, and more)

- Basic accessibility design considerations for color contrast, type size, and interactive behavior

The complexity of these will vary depending on the answers to your scoping questions, but they should almost always appear in some form, even in the smallest systems.

What design systems might need

Beyond the foundation, design systems can include other things like:

- Responsive grid and spacing guidelines and component specs

- A defined source for iconography

- Elevation styles for layering elements on the z-index

- Motion and animation details for highly interactive systems

- Advanced variable architecture to support multiple themes or color modes

- Advanced accessibility considerations for aria patterns, keyboard navigation, screen reader considerations, and focus states

- Design patterns for solving common UX problems

- Page templates for systems that serve a single product or platform

- Code snippets, fully coded component playgrounds, or integration examples for different code frameworks

- Design principles, crafted for the brand itself or the user experience

- Content guidelines for writing principles, tone and voice, or terminology

- Illustration or imagery guidelines for highly visual systems

- Governance strategy, including system maintenance and distribution

- A contribution model for large systems with a community of users

While not an exhaustive list, systems rarely include everything mentioned above. To figure out what your system needs, start by revisiting your scoping questions to brainstorm what the system could benefit from, then sort those items by impact and level of effort.

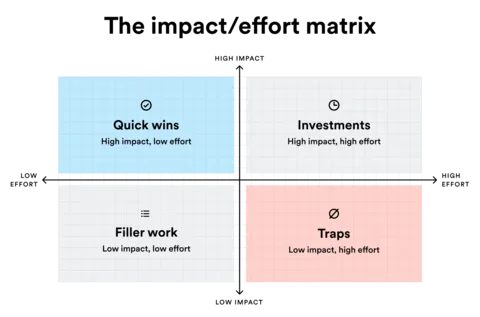

The effort/impact matrix

To help with this process, consider using an impact/effort matrix. This exercise involves brainstorming a list of goals, tasks, and features, which are then sorted into a matrix based on the work they require and the impact they provide.

- “Quick wins” are high-impact, low-effort items that should be the highest priority

- “Investments” are high-impact, high-effort items that need careful planning and resource allocation

- “Filler work” contains low-impact, low-effort items that can be completed more causally

- “Traps” are low-impact, high-effort items that should be the lowest priority (or eliminated)

Don’t do this alone! This is a great post-it sorting workshop to do with other team members or stakeholders. The more experts that weigh in, the more accurate the placements will be, and the easier it will be to prioritize more difficult items. This exercise is a great opportunity to bring everyone together to align on goals, and can be revisited if priorities shift.

Phase planning

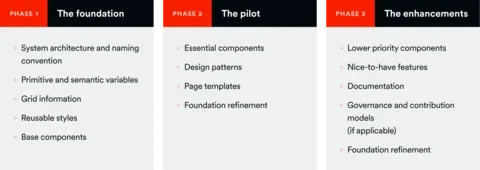

Once you’ve sorted out which items should be prioritized, organize the work into multiple phases based on what needs to be done first and what can wait until the end (or, if the project goes awry, what could be cut).

Phase 1: The foundation

The first phase of the work involves defining the structure of your system and creating the smallest pieces that will be used to build larger elements. This work is the most important part of your system, as it establishes a source of truth in your file and sets you up for painless scaling down the road. It is also the trickiest, because it’s too early for you to possibly know everything your system will need. Put careful thought into your architecture and naming convention, planning ahead for where the system is likely to grow. At the same time, keep your actual variables, styles, and components lean to start. Only add what you know you'll need, with the understanding that you'll regularly return to build on and refine the foundation as abstract ideas turn into concrete designs.

Phase 2: The pilot

The second phase should include all essential pieces outside of the foundation (components, patterns, and pages). As you complete these items, you’ll be able to further develop your foundation and strengthen the system's base. Completion of the secondary group should result in a functioning “pilot” design system, where users can start testing and implementing.

Phase 3: The enhancements

The third phase should include documentation and any items identified as nice-to-haves but not essential to the design system. This gives you wiggle room to pivot based on how the pilot system's testing goes. As much as we try to gauge our work accurately, there’s always potential for unforeseen roadblocks, so it’s smart to be prepared. Phase three work that isn’t completed can serve as a future-state roadmap for those maintaining and evolving the system.

The takeaway: Start lean and grow intentionally

A good design system isn't the most comprehensive or advanced; it's the one that functions best for the product and its users. It enables us to work faster and more consistently without introducing unnecessary complexity. A lean system with a good foundation can always grow, but a bloated system built on shaky ground rarely recovers. By starting with honest answers to the scoping questions, building a strong foundation, and adding complexity strategically based on actual needs, you'll create a practical system that can last.